We meet Meli and start our tour with a visit to the Blue Mosque

Western Turkey - Group Journal

Day 1 -

Saturday, 4 April 1998

by Geri Squires

Two days ago, several of us arrived in Istanbul on the same plane. Our first Turkish suprise was the $45 entrance fee. We had expected the visa fee to be $20. After standing in line to buy our "ticket" to enter Turkey we then stood in line to get our passports stamped. That seemed to take forever. Then it was on to the luggage carousel to pick up our bags. The final stop in the airport was to trade our US dollars for Turkish Lira. With an exchange rate of just under 250,000 TRL to 1 USD we became instant millionaires. For each $100 we got almost 25,000,000 lira!

Finally we are all in the van, stuffed in like sausages with our luggage. The route to the hotel is a mix of views, as we drive around by the Sea of Marmara. Beautiful carpets were hanging out on balconies while the building next door looked ready to collapse upon itself.

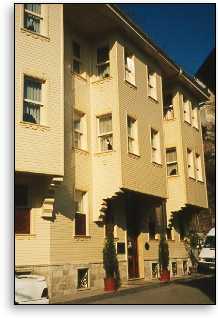

Just as I was thinking that the street we were on looked like the rougher areas of LA, we turned the corner into what looked like the outlying sections of Tijuana. Our hotel is in the midst of a poor neighborhood, looking quite out of place with its clean painted exterior. A dirt playground around the corner is only a few feet below the ledge of a cliff where cows and sheep are being guarded by some young shepherd boys. Above that is a section of old city wall.

While we were walking on our first morning in Istanbul we saw a woman leaning out the third story window of an old building, vigorously shaking out a sheet, perhaps a bedspread. She posed for a moment, looking out at the animals, and we really wanted to take a picture, but weren't sure if it was o.k. We didn't want to offend. Later we asked Meli, and she told us it would have been fine. "If they don't want their picture taken, they will let you know." It is a good idea, she says, to point to the camera and ask, "Picture?" Then don't be surprised if they, especially the children, start saying "Address, address!" They want to give you their address so you will send them a copy of the pictures you make of them. (This would have been another good thing to know ahead of time. They do not ask for money in exchange for pictures.)

Our host at the Otel Ayasofya served us apple tea and instructions on how to avoid getting lost. Although we are members of the same tour, on this first day we are still strangers to one another so we go our separate ways or two couples join together and start breaking the ice.

On Saturday, April 4, 1998 at 5 p.m. our tour is scheduled to begin. We all gathered in the hotel lobby. Everybody, that is, but Meli. Julie, Raquella, Mahmut are here but Meli's plane was late, so we started without her. The already familiar apple tea is served. Julie explained how the community journal works. Jim & Geri Squires volunteered to be the editors. Nancy Spengler agrees to be the journal monitor and make sure it gets properly passed on each day.

Suddenly it seemed as if the wind had blown the door open and Meli came in, in high heels and high gear, talking as she entered. Our first glimpse of Meli is of this burst of energy that rearranges the atmosphere around her. She poured out information and stories, including a story about the other Otel Sofya just down the street, and the missing body of the wealthy person.

Our little hotel seems to have been at the very heart of a drama, a competition between businessmen. The other hotel owners apparently concocted an elaborate scheme, first to try to get money to upgrade their hotel, then to discredit our Otel Sofya, but it backfired. They had stolen the body from its grave, and demanded money for its return. They were discovered, and their hotel is now closed. I'm not clear on what happened to the body of the wealthy person that had been stolen. Hopefully he was returned to rest in peace.

Very soon we were on our feet and trying to keep up with Meli the dynamo who set off at high speed toward the Blue Mosque. When we finally all caught up to her, she told us she deliberately walked fast to time us, and to see if we can keep up. But she promised she would always stop and wait, so no one gets lost.

There are some things she tells, and then says "remember" because it will come up later. She's not kidding. All the layers of history are spread out across this fabulous country and bits and pieces are found in all kinds of places. For us, it begins in the Blue Mosque. "Observe," she commands us, "the cascade of the domes. Look for the harmony." This is something repeated many times. The harmony in architecture is a theme we will see everywhere we go.

We don't have to cover our hair with scarves in this mosque, but we do have to take our shoes off and put them in plastic bags before we can step on the carpet. It's a balancing act, to take off your shoe between the time you lift your foot from the concrete and set it down on the carpet, then repeat with the other foot. During the trip there are a few other opportunities to practice this art. Keeping your plastic bag is also a good idea. Not all mosques have them, and you don't really want to leave your shoes piled by the door, nor do you want to carry your dirty shoes in one hand. And your shoes will get very dirty!

Meli's rule is that when we go into a site, we are to first listen to her talk and take pictures afterwards. She isn't always successful at getting us all together for the lectures, but it does help keep most of us together to have this rule.

Here in the Blue Mosque, our first lecture tells us the story of Ahmet I, who became sultan in 1603 at age 12, and at age 18 decided he wanted to build a mosque with grandeur greater than of Hagia Sophia, but was despondent because he knew of no one who could design and build such a grand structure since Sinan (1489-1588), the great architect, was now dead. Ahmet I had a wise vizier, however, who told him that he had such a man, who knew math and geometry, who was a poet, a musician, and an experienced artist in mother-of-pearl, and who had been an apprentice of Sinan.

This architect was set to the task. The grandeur of the mosque, according to the philosophy of the architect is more than just size. He imported fine marble from Anatolia, beautiful tiles from Iznik, he built 283 beautiful stained glass windows, and put six minarets around the mosque. In addition to the large central dome, there are smaller domes cascading all around. The entire mosque is a harmony of form and design, extending even to the outer court where there are colonnaded domes for the masses of people who would be unable to get inside during special events.

There is a story that goes with the minarets. The sultan told the architect that he wanted the minarets to be "fortin" or gold. The architect claimed he misunderstood, thought he said "forta" or six. So now there was a problem. The mosque at Mecca had six minarets, and it would seem that Ahmet's mosque was greater than that of Mecca. So the Sultan arranged for a seventh minaret to be built on the mosque at Mecca, making the architect responsible to see that it happened.

While marble was being brought from Anatolia, it became clear that a road was needed, and so that was built also. Tiles, the beautiful turquoise blue tiles, were brought from Iznik. The Iznik tiles are made of quartz, so they are glass rather than clay. It is from these lovely tiles that the mosque gets its popular name, the Blue Mosque.

The most difficult part was the central dome. The architect was worried about whether he would be able to accomplish it, and prayed to Sinan for help. The answer came, "That is why we have apprentices. Do what you know, and it will work."

Meli pointed out to us one of her "remember" items. In one dome there is a green medallion with a double cross overlapping. "Remember it," she says, "you will see it again."

The mosque was built during the years 1609 - 1616. Ahmet I died in 1618 at age 27. He had built his monument, as Meli says emperors do, according to his own ego.

Meli turned away from history for a moment to take a pulse of the people around her. "Why are each of you on this tour?" she asked and continued without waiting for an answer, "How many would like to learn about Islam?" she calls for a show of hands. Many hands go up, and the lecture moves smoothly from a history lesson to a lesson in religion, blended in with the architecture of the building in which we stand. The stone floor under our feet is cold, and some are feeling the cold acutely, but we all remain to hear the next part.

In Islamic belief, a human being is also a masterpiece of perfect art. We are made in the image of God, we are His workmanship, and we should not feel ourselves to be inferior to Him, but rather a reflection of Him, as well as His creation. The construction of domes in churches and mosques places God symbolically at the top - it is considered to be the "seat of God." Someone asked Meli about the placement of strings of lights not far above our heads across the mosque. "The lights," she tells us now, "are placed low to help us to not feel insignificant." (Some of us would rather have had the openness of the dome, because the strings of lights mar the beauty of a photograph, like telegraph poles and wires do in a landscape. Some perhaps, would have liked to have that feeling of insignificance against such a marvelous backdrop.)

Islam is iconoclastic, Meli says, meaning no human figures can be represented. That is why the art in the mosques is geometric, and have symbolic rather than literal interpretations of spiritual meanings. There is a sign over the entry in Arabic which Meli translates for us, "The best worship is working," a philosophy which lends value to the everyday tasks of life.

Meli told us a story about the restoration work that was done on the Blue Mosque, which took 17 years to complete. Some of the 283 beautiful stained glass windows, representing the "light of enlightenment" have been blocked by buttresses which were required to support the dome. Over the years, a great many beautiful carpets had been layered on top of each other on the floor. During the restoration a decision was made to replace them with a matching design across the entire floor. The new design is logical, the design being perfectly proportioned for a praying person to always know where the feet go and where the head goes, but to Meli it is very sad. Meli says that when she came in during the reconstruction and saw all those beautiful carpets piled carelessly in a corner, she cried for a month. "Those carpets for all these 400 years listened to the prayers and received the tears of all the people who came here to pray. And they just threw them out." We are beginning to see the passion of Meli as she shares some of her deepest feelings with us.

As we are leaving, she pointed out the symbol of the tree of life which is depicted over the door. She mentioned its significance as recorded in the Book of Genesis, and again in the Book of Revelation's letter to the church at Ephesus. It is one of those "you'll see it again" things. The tree of life is ubiquitous in the art of carpets, pottery and mosiacs of the Anatolian region.

The shops outside and near the mosque support the mosque, Meli tells us. But it is not enough money to take care of all the needs.

We play the name game outside. Still strangers to each other, we begin to know at least what name each one is called.

Dinner is in a lovely old home that has been converted to a restaurant. It has, of course, a story to tell, and Meli tells it well. The man who lived here was an artist, and created many beautiful paintings. After he died, his wife would not part with his paintings, nor let them be taken away. Her children decided to make the home a restaurant, leaving their father's art on the walls. So they did it, and then learned how to run a restaurant.

Salads, bread and bottles of water are already on the table when we arrive. The water is included, Meli says, but any other beverages are at our own expense. As each course is served, she describes what we are eating. This is her standard for the entire trip. And it's a good thing. Most of our meals are unfamiliar dishes to Americans, but all the food is delicious. Sometimes we complain that we are given too much! Perhaps our strongest complaint especially during the early part of the trip is that meals come so late. It is not that we are going hungry, it is because we Americans are accustomed to eating early and digesting our food prior to going to bed. Some of us have trouble when going to bed with full stomachs, that we do not rest well. It is one thing I don't think Meli really understood about us.

The Turkish way seems to be big meals, late at night, eat slowly, stay up even later. But maybe they have siestas in the heat of the afternoon. That is their lifestyle, and they are as accustomed to it as people at the North Pole are to 6 months of night and 6 months of sunshine. We, on our whirlwind tour, do not have time for afternoon naps, and two weeks is not enough time to adjust our eating habits quite so drastically.

But the tour is on, and there are more things to see and do and learn and experience than we can possibly cram into the days allotted to us. So we grouse about late dinners but we are not late for breakfast! There is much more yet to come. We take our vitamins, rest when we can, and try to stay healthy.