Cappadocia:

Avanos

Kaymakli

Belisirma

Guzelyurt

Western Turkey - Personal Journal

Day 9

- Thursday, 9 April 1998

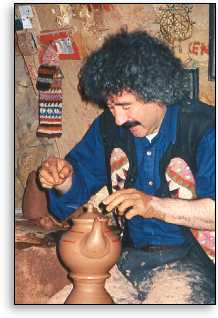

Avanos is home to Galipe, a fifth generation potter in the same rock-carved shop. Meli had arranged for him to show us how the oddly shaped little pots found in ancient sites might have been made. Under his deft hands, the lump of clay took shape and became art, in a way that pots have been created by Anatolians for centuries - on a foot-powered potter's wheel.

We made another purchase here. Two small cups with saucers, decorated with tulips, seemed small enough to carry. If weight was not a problem, we would have carried away more of the beautiful plates, pitchers, and pots. Some of the other tour members did.

It was a pleasure to walk around the village, take the unsteady suspension bridge across the Red River and see in the daylight the restaurant where we ate on our first night in Cappadocia. Donkey carts, brightly painted trailers pulled by farm tractors, and the ancient buildings of the town meant endless fascination for our eyes. Hard working farmers and their wives, laughing little boys, sweet little girls were constant photographic temptations, calling for more film in the camera.

Always too soon, comes the time to move on. The underground city of Kaymakli awaits.

Kaymakli

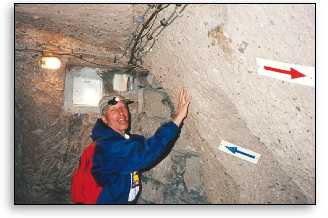

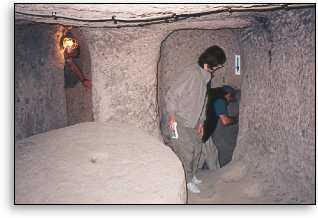

The underground "cities" are an amazing feature of Cappadocia; one writer refers to them as the 8th wonder of the world. They have certainly been a well-hidden secret. Only small portions of the approximately 40 discovered underground cities have been excavated, and an even smaller portion is available for public viewing. There are probably more cities that have not been found. Meli took us to one of the best, of which 10% has been excavated, and we will see 3%. The first three levels are probably from the Hittite days, and were used for animal shelter and food storage. During the persecutions, it grew to nine levels. Meli wanted us to think of why these cities exist, and stressed the point that these cities are not like the catacombs. "Catacombs were for the dead," she said. "This place was for the living." They had a graveyard here, but it was incidental, as a village has a graveyard.

We entered the cavity in the earth, and Jim Drahovzal the geologist was immediately checking the rock wall, wearing his headlamp. We got a great laugh at his expense, but it was joyous laughter. We referred to Jim as "our" geologist, and some of us constantly bombarded him with questions about the terrain. He was a very good sport and a great teacher, willingly answering with as much knowledge as he had, which was considerable. He had studied the region ahead of time, and knew what to look for.

Meli quickly led us deeper into the tunnels, lecturing at each stop along the way. She pointed out the lack of soot on the ceilings in what was probably sleeping quarters for a family, indicating that the people lived in near-total darkness. Candles or torches would have consumed too much of the precious oxygen. Soot was found on the ceiling in the birthing area where light would have been a necessity for cutting the umbilical cord. To keep the mother and the newborn baby warm, sheep would have been brought in, and the warmth of their bodies would have helped to heat the room. A cross on the wall may have been there as a symbol to give them strength and courage. Childbirth often happens spontaneously when stressful situations such as war or natural disasters occur.

There were storage areas for food and for wine. The kitchen was located beside the well and just at water level, so that it would have been easy to draw water for cooking and drinking. Bulgur, sundried meat, apples, apricots, oranges and grapes could all have been stored in these rooms, and been available in good times or in bad. It seemed that people did not only come here to hide for a few days; but 1100 people could have lived here for up to a month easily, as they hid from their enemies.

The presence of a church suggests that it might have been used not only as an escape during times of war, but also as a secret place to practice Christianity during ongoing times of persecution. The church is marked with a cross on the wall, and in the center is a a chunk of stone left standing as they carved the room out of the rock, probably a communion table. The early church had very few rituals, and sharing bread and wine in memory of Jesus was one of the most significant. Meli suggested that wine services would have a sedative effect, a desirable state for people forced to hide here for long periods.

The entrances to these cities were well hidden. Some of the underground cities are built under villages, with exits from inside the homes directly into the earth beneath. Round stone doors could be rolled into place behind them, and could be opened again only from the inside. Some had zigzag escape tunnels, so that the people could have come out on the other side of the hill and slipped away, unseen by the attackers. Some had tunnels connecting one city to another. Ventilation shafts were well placed and well designed.

The Christian community that was cradled here in the early centuries was nurtured and grew in these rocky undergrounds and in the rock churches we saw aboveground. Christian theology books refer to the Cappadocian Fathers, including three Christian leaders of the fourth century who were vitally important in protecting the true doctrines against heretical beliefs that so readily sprang up. St. Basel, St. Gregory of Nyssa and St. Gregory of Nazianzus were the defenders of the concept of God as "three persons in one substance" or as we sing in American churches today, "God in three persons, blessed Trinity." Basel and the two Gregories are the ones whose images we first encountered at Chora Church in Istanbul.

But all of that is history, and Islam has replaced Christianity in Anatolia. The churches and the underground cities are empty museums; prayers to God have been replaced by prayers to Allah, and the Bible has been replaced by the Qur'an. Instead of the teachings of Jesus and Paul, the people listen to the teachings of Mohammed and Rumi.

While we were underground, Meli spied a young just-married Muslim couple. The lovely young lady was gracious to show us her traditional gold necklace, hiding beneath her scarf. The tradition is that the young man gives a necklace of gold coins to the bride. It is her security, in the event the marriage fails or something happens to him. In reality, it is often a fallback for the family to use in difficult times. The glow of the gold coins and the happy glow in the bride's face were a wonderful contrast to the gloomy darkness of this underground hiding place.

After duck-walking bent over through the tunnels, we were happy to stand up straight in the sunshine again.

As we drove through the countryside, Meli pointed out how freshly planted fields were marked by seven stones piled on top of each other. This is a signal to the wandering shepherds with their flocks, so that the new growth is not trampled. When the field has been harvested, the pile of rocks is knocked down, and the animals are allowed to graze freely. There are no fences. One or two shepherds, and two or three of the wonderful Turkish Shepherd dogs accompanies the flocks that we see. The fierce-looking spiked collars worn by the dogs is protection against attack by wolves.

Cappadocia seems a dry and dusty land, interspersed by small trickles of streams, and the Red River is like a shining ribbon running through it. The fields in April are still dormant, and dry brown grass is the forage available for the herds. Two weeks earlier there was snow on the ground here. In another month, it will probably look very different, green with spring growth.

Meli talked about feudal and agricultural reform that is happening here. Efforts are being made to teach the farmers progressive ways, and cooperatives are being established. She told the story of a woman who decided to try to market the delicious Cappadocian potatoes to the Germans. The Germans, however, did not like the small, yellow, less-than-perfect potatoes. They wanted the white American-style potatoes. Undeterred, the woman managed to acquire some seed potatoes from America. Unfortunately, along with the potatoes came the potato whitefly, previously unknown in Turkey. The struggle continues.

(When we were in Samos, we had some of the best french fries we'd ever eaten. We talked to the restaurant owner, and he told us of buying them frozen in bulk from Holland. They are yellow potatoes, and make much better french fries than the white ones. The lady in Anatolia needs to keep doing research. With the persistent Turkish determination that we have seen in Meli, I am sure she will eventually succeed. The Dutch apparently figured out if you can't sell something one way, try another.)

In the distance, we saw the white peaks of Erciyes Mountain, which is usually veiled with clouds. Meli was delighted. "Like a bride, she usually hides her face. She is being bold for us," Meli said.

Belisirma

Our bus took us through more dramatic countryside, past more crumbling rockhouse villages, and into the very poor village of Belisirma, on the side of Melandis Mountain, where we ate lunch at a restaurant called the "waist wrapped around with golden thread." Meli had mentioned it to us when we were in Istanbul, when she talked about the "belted stone" neighborhood. Place names are very colorfully descriptive in this country.

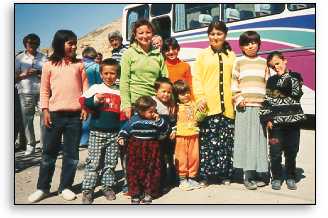

As our bus pulled into the little village, children came running from all directions. They know Meli and were eager and happy to see her, and to see us. Cameras came out, poses were struck and addresses were written. Little Damla Gorur attached herself to me and followed me everywhere I went until we were back on the bus again.

To get to the restaurant, we walked up and down the hilly streets and across the Melandis River, which Damla told me, has fish. She also pointed out the chicken with the baby chicks, and told me the Turkish words for each. I later learned that she has a speech defect, and my trying to understand and echo her Turkish was just impossible!

Meli told us that the food we ate at the open-air restaurant beside the river, was the same as what the villagers would be eating that day. A simple vegetarian meal of salad, fava beans and bulgur, it was delicious and quite satisfying.

The village houses are made of stone and look very old. But on many roofs satellite dishes point skyward, and perhaps poverty is only a relative term. The children were all dressed in bright colorful new clothes. Mahmut told us it is because of the holiday. Everyone gets new clothing for Kurban Bayrami.

When we left the restaurant, we had opportunities for burro rides, and some of our less-than-healthy members were given rides back up to the top. At one house we passed, Meli pointed out the sign above the door. There is a Christian cross, a date written in Greek, and then in Turkish an Islamic blessing "MASSALX" or "May God's blessings be on you."

We reconvened at a home, where we all were packed into a small living room and tea was served. Damla eagerly helped. We were invited to ask the family questions, and to learn about their lives in the village. The mother of the home showed us some of the flat bread that they make in the fall and stack up. Dry and hard, it does not decay and is made palatable by a bit of water and warming on the stove. Samples were quickly passed out to us so we could see that it was very good to eat. She also showed off her necklace of gold coins, and even took it off for female tour members to wear briefly for photo opportunities. As she readjusted her scarf, we caught a glimpse of her hair, red with henna. We left this warm and gracious home with a sense of reluctance - "a spoonful of honey in our mouths."

Our next stop was our hotel in Guzelyurt. A former monastery, later a girls' school, it had an enormous auditorium where we gathered for a glass of wine, Beethoven's Ninth and a Meli story. She had found this place was quite by a serendipitous accident. She had a tour that could not get into the underground city that we visited, and so she detoured to bring them to a different underground city, near here. It was raining so she couldn't have her planned picnic. Everything seemed to be going wrong. But Meli knew she would find a way. She did. She was led to this place, and the resulting dinner was so wonderful, each time she returns here is a solemn, emotional and almost sacred occasion for her. Meli talked about how the people of this village lived comfortably side by side, Muslim and Christian together as family. The population swap dictated by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1927 ripped the community apart and took the Christians all to Greece. Even today, there are Greek Christians who tell their children who visit Guzelyurt, "Say hello to aunt so-and-so." They were very close, like family, and differing religions did not keep them from loving each other. With Meli, we drank a toast to peace.