Istanbul:

Basilica

Cistern

Aya Sofia

Topkapi Palace

Western Turkey - Personal Journal

Day 5

- Sunday, 5 April 1998

Our second day with Meli began as we left the hotel where she directed our attention to a fountain in the wall. It is significant to Meli. She wanted us to understand that an old and valuable object could be taken for granted in the "busy-ness" of everyday life.

Basilica Cistern

We were led beneath the city streets into the subterranean world of the Basilica Cistern, made famous in the James Bond movie From Russia With Love. It is one of many cisterns that lie hidden below the city. Meli drew us near the edge of a walkway so that we could hear her. Her first lesson is "Listen." Dutifully we fell silent and listened. We heard the echoes of water dripping in the cavernous silence and a spell seemed about to be cast in the pause. But Meli's voice broke the quiet, as she began to tell us the importance of the capital to three regimes: Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman. If you fly over the city, you will see that it lies on 2 continents. When you walk on the streets, you can see living history. Follow a trail of that history as you descend the narrow, damp, steep steps into the cistern. They are made from antique stones used by Romans and Byzantines, and recycled to make the steps, the pillars, and the walls of the cistern.

Here, underground, you find the lifeblood of the city. Above ground, the city is surrounded by water - the Black Sea, the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara - "garlands of water" which is all salty. There has never been fresh spring water anywhere in the city, so its aqueducts and reservoirs predate the Roman era. The water is brought from lakes as near as 4 or as far away as 80 kilometers.

Some of the old cisterns have been converted into business enterprises, such as restaurants or car repair places. This one is a tourist enterprise. The seriously crowded city would surely benefit from a subway system, but one cannot be built because it would destroy these underground museums.

Meli told us there are 1001 pillars in this cistern. Then with her little smile, she told us what that means. Reminding us of the 1001 stories of Aladdin and his magic lamp, she told the meaning of certain numbers to the people of Anatolia. The number 40 means "many." The number 72 means "more than many." And the number 1001 means "so many it is hard to count them."

Someone spied fish swimming in the waters and interest turned in that direction. Meli told us that they have become a specialty in French restaurants. They may be the same kind of fish caught elsewhere and sold for a regular price, but they are on the menu as the fish from the cisterns of Istanbul and sold for high prices.

Deeper in the cistern, we paused again to experience the sound effects. Meli asked us to sing, but we had no real singers among us. Julie volunteered to sing and did quite well, but the effect Meli wanted calls for a soprano whose voice could crack glass to get the vibrations flowing here. But we got the idea, and together we sang "Amazing Grace."

"Istanbul," Meli said, "is like an old woman trying to look good." Surely the city is old. Looking good will take a great deal of cosmetic improvement. But here and there we can see the beauty. The Christian Byzantines who built this cistern used old Roman pillars, capitals, stone blocks, whatever they could recycle, and put it together with masonry. Bricks are used to make it come together perfectly. Iron bars make it earthquake proof. Terra cotta is used to line the walls and prevent leaking. There is seepage from above (the dripping we hear) as ground water seeks a lower level. When this was a working cistern, one of the concerns was the water pressure becoming too great (i.e. too deep) because of the seepage. If the water rose too high, the people used buckets to haul the water out so that the right level was maintained.

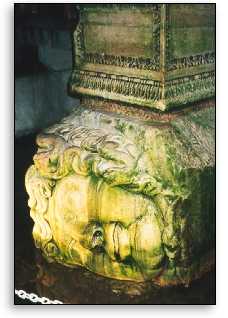

Down one walkway, we came to Medusa heads, recycled as part of the pillars that support the roof. One is sideways, another is upside down. The people didn't care about the Medusas; they just wanted the marble block. No effort was made to position them as adornments nor, as the pagans had used them, as protectors. (Remember the Medusa. We'll see her again.) Meli described her as a polytheistic deity that had been humanized. She is the Medusa of Greek legend, whose hair is snakes, and whose unique blue eyes you must not look into. "The eye," says the legend, "can turn you to stone." We will see the blue eye in tourist shops everywhere we go in Anatolia, and in homes and businesses. The legend continues, "If one looks upon it with evil in one's heart, the evil will be returned upon oneself." Meli gave each of us a small souvenir of this lecture - a small blue "evil eye" to be worn on our lapels. The little pins were noticed later on many lapels. But not everyone wore them.

The cistern has an image of mystery in the minds of the people. There is an old legend told above ground that the cistern is so large that if a fleet of ships were deployed here they wouldn't see each other. The stairs that descend into the depths used to be wooden, not the slippery marble we so carefully negotiated. There were also small wooden boats used by the workers to check and maintain the construction. Romantic young men who brought their sweethearts below also used the boats and lanterns. It was an ancient version of the drive-in movies, Meli says.

We exited the cistern through the gift shop, where we spotted Meli's book on Ephesus. But it is a coffee-table hardcover book, too heavy to buy this early in our journey. "Whatever we buy," we reminded ourselves, "we have to carry."

Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum

Above ground again we headed for the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum by the Hippodrome. Here Meli pointed to an office, above the doorway was the "evil eye" of Medusa. We were taken into a room of the museum where apple tea and pastries were served. We relished the break, but there was no break in the lectures. Meli had a great deal to tell us, and this was a good time. We sat with our tea and listened.

Turkey, Asia Minor, Anatolia - many names have identified this geographically strategic territory down through the ages. The oldest name, Anatolia, means the "place where the sun rises" or the "place that is full of mothers." The word Anne means biological mother. The word Ana means a loving nurturing woman. It has also been the home of the mother goddesses. This will be made very clear by the time we get to Ephesus. Catholics and Eastern Orthodox people as well as readers of the apocryphal literature, may be aware that the mother of Virgin Mary is reputed to have been named Anne.

"We must look at the roots to understand behavior," Meli told us. We heard stories of two types of movements of people - invasion or immigration. We hear about the Trojan War, Jason and the Golden Fleece, and Czar Nicholas coming through the Bosphorus.

She talked about how Xerxes, in the 5th century BC when the Persians expanded their borders, built abridge of boats across the Bosphorus to the European side. Alexander the Great built a pontoon bridge to cross in the opposite direction, from the European side to the Asian side, on his way to conquer India.

Julius Caesar crossed the water with pontoon bridges that had been made in Rome before he left there. When he reached the center of Anatolia, he left his famous quote, "I came, I saw, I conquered."

By 300 AD corruption was infecting the Roman Empire. There is a story of four competing leaders who were fighting against the Goths. The four argued with each other, three fought and the fourth one watched. Afterward, one was limping, one had lost an eye, and one had lost a hand. Only the watcher, Constantine, remained whole. He built Neo Roma, New Rome. It was the end of the Byzas era, and the city was soon renamed Constantinople.

In the 11th century, the politically motivated Pope-ordered fourth crusade went quite astray from attempting to recapture Jerusalem from the invaders from the east, and conquered Orthodox Christian Constantinople instead. The army was populated by thieves and rogues who expected to receive eternal salvation for their services. The great treasures and religious relics were carted off to Rome, and the city was a shambles.

In 1453, the Muslim Turks (who adopted Islam when they passed through and conquered Persia) took the city in one day. They had built fortresses to cut off the food supply, and moved their boats overland to enter the Golden Horn. On their way along the road, they saw a sign that said, "Stamboule" and that is what they called the city. What the sign was actually saying was "to the city."

In World War I, this strategic location became "the desire of all nations," and every country on the winning side wanted to own or control Istanbul and Anatolia. A man known today as Ataturk arose, led the inhabitants to victory against all these armies, and established the country we now call Turkey. He moved the capital to Ankara. (We will learn more about Ataturk when we reach that city.)

"The worst thing in the world," Meli believes, "is ignorance." She warned us to follow up with questioning so that we do not have misconceived ideas. "There are two reasons for ignorance. One is not knowing that you need to know. The other is having been intentionally taught wrong things."

The story of the Oklahoma bombing and the immediate reactive speculation of the American media ("It must be Muslims.") is an example used by Meli. In fact the bomber turned out to be American born, and embarrassingly to us, Meli's point is well taken.

"You can understand religion by seeing its culture. One creates the other," Meli said. "Let old notions be laid aside. Be willing to understand different cultures, to understand the behavior of people."

Yurt (tent) was a word that meant "homeland" to the nomads. Wherever the yurt was, that was home. This is basic to the culture of the people of this land. Perhaps Meli said, "Remember the yurt." We did see a black tent later, as well as a flock of the black goats whose hair provides the basic building material for yurts.

Mohammed, the father of Islam, banned anthropomorphic representations. "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image," one of the Ten Commandments, was very important to Mohammed and has influenced the art that is seen in tiles, pottery, carpets and kilims everywhere.

One commonly seen symbol is the crescent, which was important to the Selcukian Turks who came from central Asia. It is seen today on the Turkish flag. (Later in our trip, when we landed in Athens in the pre-dawn, a crescent moon hung over the city, close beside it the morning star. The emblems of the Turkish flag might well have been cut out of just such a night sky view and laid upon the red background, which signifies the blood shed in this war-torn country.)

Turkish or apple tea is usually served in little tulip-shaped glasses. Meli told us that the Turkish word for tulip, backward (right to left) reads God. Tulips originated in Turkey, not in Holland, and Turkish art frequently includes the tulip.

Another important representation in Turkish art is the tree of life. Although it is not restricted to Turkey, and is known to be a favorite in many parts of Asia, here it seems like a part of the lifeblood.

We were led into the museum, and for two hours we heard and saw more history than we could possibly absorb. I'm sure that each of us came away with different impressions, there was so much to see. The pages of history fluttered, the winds of time blew past us too quickly. Brief notes do not begin to record the stories told by carpets, kilims and ancient artifacts, as we spent a little time wandering on our own. Some told of seeing a 13th century astrolabe, and an 18th century device that allowed the traveling Muslim to accurately locate Mecca.

Meli pulled us together again, and we descended to the next level. She walked us past several dioramas that dramatically and visually told the story of the change that happened to women, as the culture changed. We began with the nomadic tents, where we saw the simple life. It was a matriarchal society, Meli told us. The women were the ones who decided what to plant and when to move. They dominated the culture, and carpets were a big part of that.

A nomad baby was born on a carpet. All his life, he would sit on carpets, sleep on carpets, and live on carpets. When he died, he would be wrapped in a carpet for burial. The women used the wool from the sheep or goats to make the carpets. They spun the yarn, died it with natural dyes from flowers or plants or roots, wove the kilims, knotted the carpets, and created the designs. Experts can tell many things about a carpet or a kilim, by looking at the colors and the design. A design was passed from mother to child, and certain designs identify certain groups of people. The geographical location can be known by the colors because the women used what grew in their area. The type and quality of material (wool from sheep or goats, cotton, silk) are more keys to the carpet's geographic origins. But the carpets, Meli told us, are like the ancient fountain near our hotel - taken for granted and neglected.

As the people settled into villages and cities, the role of the woman changed. By the time of the sultans, women were no longer the ones in power, but had become decorative symbols in luxurious palaces, and the pawns of men.

"Religions," says Meli, "are built on previous ones, or replaced by others." Religions are built to "suit the needs of the people. The purpose of religion is to help the people be happy."

All of this was before lunch! With our heads spinning, we dashed over to The Pudding Shoppe, which has a history of hippies and other quirks that I don't quite remember. I wasn't taking notes, I was eating!

After lunch we were off to the nearby Hagia Sophia museum. The Hagia Sophia is considered by many to be the greatest edifice for Christian worship ever built. Perhaps I was overburdened with the morning's learning, but somewhere here I stopped taking notes. I was, I think, in a state of shock as I went into the cool interior of the building and saw the faded grandeur, the mosaics that glorified Mary above or equal to Jesus and honored the dead emperors and conquerors.

Here was a place where early Christianity had taken root, where many faithful followers had died for their faith. This was the church that was built first by Constantine, and rebuilt by Justinian when the first one burned. It had "lost its first love," as evidenced by the story told in the mosaics, with worship shifting from Jesus to Mary. Small wonder then, that it had fallen into the hands of the Muslim Turks, who had turned it into a mosque.

Secular minded Ataturk, who wrenched the nation into existence and banished religious rule along with the fez and the veil, had taken this building from the hands of the Muslim Imams and made it a museum. It stands in tragic disrepair as a testimony to its history. Who can read the meaning behind it all? It stands in dramatic contrast to the Blue Mosque standing a few hundred yards away, which we saw just yesterday, clean of icons and goddesses and emperors. I am overwhelmed, I don't know how to feel or react. It doesn't help that we are swept along so quickly to our next experience, the Topkapi Palace. Fortunately we have seen the Topkapi palace already, and I can just drift along.

Topkapi Palace

On our second day in Istanbul, we had joined with Jim and Becky for a day's meandering around Topkapi palace. On the tip of the peninsula, it looks out on the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara. Mehmet II erected the original structures as his own palace after he conquered the city in 1453. Additional structures have been built through the centuries as succeeding sultans expanded and added to the wealth of the Ottoman Empire. It was converted to a museum in 1924.

The wealth of a nation on display is always breathtaking. Lavish use of gold on the walls and ceilings, elaborate art and artifacts, beautiful stained-glass windows greeted us in the living quarters of the sultans. The harem consisted of 400 rooms, housing thousands of women and children. The decay of the empire began in the harem, where the women competed to be the mother of the next sultan.

On display here are many interesting things, jewels as big as rocks, elaborate furniture, dishes, clothing and weapons. Among the luxurious items rests a few strange things, such as bits of Mohammed's beard, and one arm encased in gold, said to have belonged to John the Baptist. It is perhaps the only surving relic of the early days of Christianity in a city that once claimed ownership of more relics than any other area. The raiders of the fourth crusade carried most of the relics off along with other treasures of Hagia Sophia. Rome is the place to see Istanbul's Christian history. Topkapi holds a small portion of the Ottoman Empire treasury.

When we left Topkapi, we stopped at a lovely hotel (too bad we're not staying here!) to enjoy their garden patio with some refreshments and conversation. After a little while, I slipped away and went alone back to the Hagia Sophia. It was closed by this time, and I could not go in to be alone with my turmoil, so I walked outside, fending off the carpet salesmen. They could certainly see that I was interested in the museum, and helpfully told me it was closed, but that I was welcome to pray in the Blue Mosque. When I asked them if there were no Christians in Istanbul, they quickly told me "There's the street." They no longer wanted to talk to me. I was grateful and walked on alone with my thoughts.

At 7 p.m. we had a group meeting in the lobby that dragged on. Most of us would have preferred to have dinner first, then the meeting and a chance to talk about our "culture shock" of the day. At 8:45 we gathered again to walk to the fish market for dinner in Kumkapi at Dogen restaurant. The food was good, but we were "entertained" by gypsies who played (too loudly) something they called music. It was unfortunate. I think there is probably some very good music in Istanbul. What we heard on the radio at night was mellow and gentle, lovely stuff. Some CDs that Jim bought later and brought home are definitely preferable to the sounds we heard that night.