Ankara,

Hattusas,

Cappadocia

Western Turkey - Personal Journal

Day 7

- Tuesday, 7 April 1998

About 6 a.m., we got dressed (there aren't any showers on the train) and Jim shaved in cold water. We then made our way to the dining car for breakfast. Another group had been told to be there at 6:30 but they came later, and when we arrived at our appointed time of 7:00, the tables were crowded. It was a minor nuisance; we still managed to get a good breakfast before the train arrived in Ankara.

Ankara

We milled around the train, trying to claim our baggage, and get to the bus. Meli gave us the bad news. We would not be able to see the wonderful Ankara Museum of Anatolian Civilization. Because of the Bayram holiday it was closed. We had a brief tour of part of the town and the capital buildings.

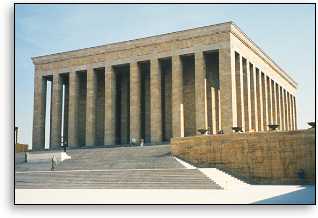

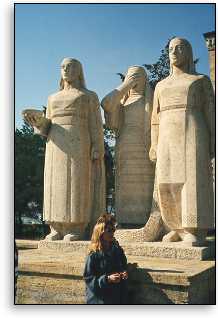

Then we entered the Ataturk Memorial Park, where his tomb is located. Meli told us a long story of Ataturk, interrupted once by the changing of the guard outside the building we were in.

Her lecture ended with an emotional reading from Ataturk's speech at the Anyac memorial in 1934.

"Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours. You the mothers who sent their sons from far away countries wipe away your tears. Your sons are now in our bosom and are at peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well."

After the lecture we had some time to walk around, go into the building where Ataturk's bones rest in his tomb, and deal with a new and unexpected set of emotions. I have a new respect for the accomplishments of this small nation, and something akin to awe at the stature of this man. Meli's devotion to his ideals is obvious. The driving force behind her passion and zeal is beginning to be revealed. I cannot express more eloquently than what Dave Pratt wrote in our community journal:

Turkey's 20th century hero, Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) brought about a huge revolution in Turkey between 1915 and 1938:

- Driving Britain, Greece, Italy, and France from Turkish territory, to consolidate the present boundaries

- Bringing about a secular state under a democratic form of government by removing first the political power and then the religious leadership from the sultan, and replacing religious courts with civil courts;

- Emancipating women

- Introducing the Latin alphabet and phonetically adapting the Turkish language to it;

- Eliminating many Arabic and Persian words, replacing them with words with Turkish roots

- "Outlawing" wearing of the fez and veil

- Introducing the metric system

- Replacing the lunar calendar with the Gregorian calendar.

On the steps in front of Ataturk's tomb were his words, "Sovereignty belongs to the people unconditionally." Meli summarized an important struggle in 1990's Turkey by contrasting these words with the view of the Muslim fundamentalist; "Sovereignty belongs to God unconditionally."

Since we could not see the Museum of Anatolian Civilization, Meli came up with an alternate plan, involving a long bus ride to the excavated ancient (7500 BC) Hittite city of Hattusas.

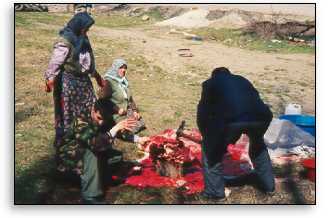

As we were leaving Ankara, we passed family after family in the process of sacrificing or butchering the ram for Bayram. Kurban Bayrami is a memorial holiday based on the story of Abraham and Isaac. Abraham was asked by God to sacrifice his only son, Isaac. When Abraham demonstrated his willingness to be obedient, he was stopped at the last moment and shown a ram with his horns caught in the bushes. The ram was sacrificed instead of Isaac.

The Muslims, who trace their connection to Abraham through Isaac's half-brother Ishmael, remember this event every year by sacrificing a ram, and giving the meat and the fleece to charity. It is a weeklong holiday, celebrated around the world. Many Muslims take this opportunity to make a trip to Mecca.

During the week, we heard the news about some people caught in a stampede in Mecca and trampled. They were participating in a Bayram ritual called "stoning the Devil." (Many months later I learned that Muslims are taught that the nearly sacrificed son was Ishmael, not Isaac. Then I understood why this was such an important holiday for Islamic people.)

A little out into the country, Meli asked if we'd like to stop when she saw yet another sacrifice in progress. A positive chorus brought the bus to the side of the road. After Meli had requested and received permission from the family, Americans with cameras poured out to capture this amazing sight. The ram skin had been separated from the carcass and was serving as a groundcloth to keep the meat clean, as they worked right on the ground.

Shortly after we disembarked, one of the scarf-clad young women ducked into the house and came back with her own video camera to take pictures of us. She and her husband are guest workers in Sweden, and were home for the holiday. Her English was excellent.

A bus lecture filled in some of the travel time toward Hattusas. Meli talked about Islam, and why the Muezzins sing the call to prayer five times a day. Somehow the timing is related to avoiding alignment with old pagan practices of praying to the sun, at dawn, noon, etc. The call to prayer takes up the time that the pagans used for prayer, so the Muslims are not praying at those times, but preparing to do so. It seems like the plan backfired, because everyone's attention is still drawn to those certain times.

Meli talked about the differences in environment in Anatolia and how those natural differences affect the people who live there. In the West, the people live near the sea, have good weather and an abundant food supply. The character of these people is friendly, easygoing, and they are secure but volatile.

In the hot and dry center of the country, the people live in a static society, and are orthodox and traditional. They have the attitude, "If we are good to God, he will be good to us and send rain when we need it."

In the East are the high mountains. The people, utilizing three levels, shift their animals up and down the mountains for grazing, depending upon the seasons. Infants die easily in such harsh conditions, but the survivors live long lives. They bond to each other to survive and become clannish. Outsiders are not easily assimilated, but have to earn respect.

"What we don't know," Meli says, "is God. What we can do, is progress." She talked about Çatal Höyük, the world's earliest social settlement that has been excavated. The people had pottery, woven clothing, seals depicting ownership, and judges, indicating that class differences existed even then. She talked about society as a pyramid, with religion at the top, judges or rulers next, and the ordinary people as the wide base. She discussed how two societies interact when they come together, and one has more than the other. This reflects back to her statement in the museum near the Basilica Cistern, about the movement of peoples being immigration or invasion.

One society may try to take what the others have by invasion, or they might immigrate and share. The two societies might have very different values. She told of us two different ones. In one women were valued and divorce was punished. An old message has been uncovered that a man wrote to his mother: "Mother, I love you so much. You are more precious than iron, and more beautiful than bronze." In the second society, women were treated as collateral. Such societies would clash for reasons beyond economics.

Meli talked more about the mother-goddess image, how differently she was perceived by different societies, and became stylized as people's independence grew. Then the god of war arose and became head of all. The ruler started to play the role of god. The people wanted to bring peace back, and the mother goddess was re-established. They wanted to have self-sustained, self-sufficient groups.

Hattusas (Bogazkale)

As we approached Hattusas, Meli told us how German archeologists had discovered the site, and that the best pieces are in Germany. But we are excited about being on the site itself.

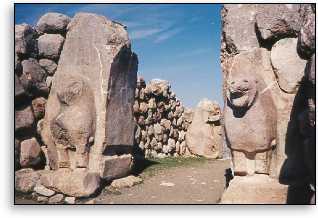

Brittanica Encyclopedia identifies Hattusas as "the ancient capital of the Hittites, who established a powerful empire in Anatolia and northern Syria in the 2nd millennium BC. The earliest settlement in the city area dates to the 3rd millennium BC, in the so-called Early Bronze Age. There are no written documents that would reveal the identity of the first settlers. The earliest written sources that were found at Bogazköy are clay tablets inscribed in cuneiform writing in the Old Assyrian language. They attest the presence of Assyrian merchants on the site, which at that time was called Hattus. With the downfall of the Hittite Empire (c. 1190 BC) the city was destroyed; traces of burning are found in all parts. The site, it seems, remained vacant for a long time. The next settlement, mainly on Büyükkale and in the lower city, was in size and layout much more modest than the Hittite capital. Through pottery and other finds, this settlement is linked to the Phrygians, to whose kingdom the region belonged in the 8th century BC."

This is a place no other ETBD tours have gone. We are all enthusiastic, but the bus ride was very long, and our time on the site turned out to be quite short. Just before we reached the site, we went through a small village that was a photographer's dream. But we did not have even a minute to pause there. It was one of those "spoonful of honey" experiences, that made us want to return for more.

Young men were at the site, selling carvings of ancient images from the local green rocks. "I carved this myself," they told us. Jim was particularly captivated by one of the lions. Behind us was a gate to the city, guarded on each side by huge carved lions. A "group photo" was taken here, and then we rushed on to the next spot. Through the defensive wall runs a tunnel and we felt our way through the darkness to the other side. It was in the dark, damp and slippery tunnel that Jim acquired a skinned knee and ripped pants - but he kept his cameras safe!

The bus ride from the archeological site to our next stop, Cappodocia, was very long. Meli proposed that we each give a brief history of why we choose this tour, and express what we feel we gain by travelling. Some very interesting stories were shared; none were more interesting than Meli's. She told her story last, and it began with the origin of her ancestral family.

They were Jews who converted to Islam, probably for survival rather than personal conviction. Meli told us about the "people swap" early in the 20th century that the European powers (Treaty of Lausanne) thought was the solution to squabbles between Christians and Muslims. All the Christians in Turkey were moved to Greece, and all the Muslims living in Greece were moved to Turkey. This was an "overnight" move, and people lost all they had. On both sides, they were forced to live in tents while housing was constructed. Meli's Jewish-Islamic family was moved from Greece to Turkey, and suffered greatly. (The same kind of "people swap" was done in India in 1947, creating the Muslim country of Pakistan, and is depicted in the movie Gandhi.)

Meli told us about her own fascinating journey through life, her time as an exchange student in America and her realization that "My country needs a Joan of Arc. I'll be one." She married a governor, but realized this was not the right way for her. In her divorce she asked only for the children, and no financial settlement. It meant that she and the children lived in a nomadic tent for two years, but independence was important to her.

Cappadocia

We arrived in Cappadocia just in time for dinner at a restaurant on the Red River in Avanos, and it was quite dark by the time we arrived at the Green Motel. Meli had searched out a family who were renting rooms but wanted to preserve the old ways of the village. Over the years the money for the tours that she has brought here has enabled the owners to build up their business quite well.

There are a couple of problems that still need to be addressed, however. Since the motel is carved into the rock, cold was a problem for us in the still-early season. Perhaps in summer this is an advantage. The more serious problem is the shortage of appropriate traps ("U" pipes) in the plumbing in some of the bathrooms. After a few flushings, the odor of sewer gas was almost unbearable. In spite of the cold, we slept with the window open. That was the night I came down with a sinus infection, joining some of the others who were already ill with various virus afflictions. (Our tour plumber later advised us it would help to block the sink drain, and that wet toilet paper made an excellent block.)